|

|||

... |

|

|

... |

|

Charles Platt is best known for his writings in Wired magazine. His career started in England in the mid 1960s as he worked with Mike Moorcock on the New Worlds magazine as a writer, editor and designer. He has published some 40 books of fiction and non-fiction since, worked as an editor in major publishing houses and is always looking to challenge the status quo and push onwards. I had the pleasure of asking him a few questions about his history with New Worlds, thoughts on the genre, publishing industry and fringe sciences as well as talking about his friend and once-collaborator, Barry Bayley. The interview was conducted on phone, from Helsinki to Arizona, on the 4th of July, 2000. |

... | |

sound clips clip 1 (00:12) ... |

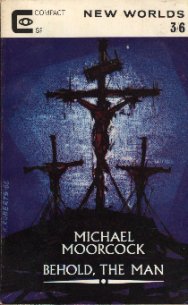

It all began in England, in the early 1960s. You started writing fiction and nonfiction around that time. Could you tell me a bit of those early days - how you got started and interested ? My main subject at school was mathematics, but I also wrote short stories in my English classes. I started sending them to science fiction magazines in England shortly after I graduated from the British equivalent of high school, and dropped out of college. This just happened to be at a time when Michael Moorcock was taking over the only British science fiction magazines. When a new editor takes over a magazine often he wants to find new writers, so I was fortunate in that I was sending my stories at that time. And he kind of 'discovered' me (chuckles). Then I moved to

London and I found by chance I was living in the

same neighborhood in Notting Hill as Michael Moorcock and his friend

Barry Bayley.

So that was when I got to know Barry, around

1966. At that time Barry was still writing comic strips

for - I think - Fleetway Publications but also he

was writing these really good short-stories for

New Worlds magazine and I really admired his

ideas. So we always kept in touch even after he left London and moved to the North of England. |

... | |

| ... | It seems to me you two share quite a bit; there's this interest in idea-driven pulp science fiction and I think you studied economics and Barry wrote parts of a book on the subject, and then there's all this visionary, or fringe, weird sciences that both of you seem to have an interest in.. That's true, that's a very interesting observation. I was wondering if this was something you were aware of during that time already.. No I wasn't

actually. It's very perceptive of you.

In 1966, there was less plausible "fringe science" to catch my

interest. The only examples I can think of were the Hieronymous Machine,

described in John W. Campbell's Astounding Science Fiction magazine, and

dowsing rods, also described in Astounding. I built a Hieronymous machine,

which did not work. I tried dowsing rods, with inconclusive results. Also

I tried the standard deck of Zener cards, in telepathy experiments. These

proved nothing. So I remained very skeptical.

The

difference between Barry and myself as regards to

the fringe science is that I had a pretty solid

science education and I don't think he did. So

often he would be just one step more likely

to believe things that I thought were probably

not true (chuckles). |

... | |

... |

Like he wrote this whole non-fiction piece about how the force of gravity may be - instead of an attraction force, a repulsion force. And the repulsive effects of stars are pushing us down to the surface of the Earth. I thought this was a great idea, but I had a strong feeling that a concept as basic as this must have been thought of before, and must have been disproved. So I went to some friends of mine who had other friends who were real physicists and one of them was kind enough to write this long rebuttal explaining to Barry why this isn't so, and also pointing out that this idea had been first suggested about a 100 years ago. And I thought "oh yeah I kinda had a feeling Barry was a little too far out on this." But he wouldn't admit defeat and said "oh that's just typical of the scientific establishment. I knew they weren't ready for my ideas." |

... | |

| ... | Barry's work was more closely associated with the past pulp than what most others wrote for New Worlds, separate from much of it. Do you remember if there were any attitudes towards this traditional, pulp science fiction in those days? No, but I think he never got sufficient admiration and respect because it had that quality. You know when your first training is in a particular field of writing, it kind of imprints you in various ways. It's like if you're a musician and you first learn one instrument - if you try to play other instruments after that you still have the same kind of patterns you learn. And Barry's first training was writing these adventure comics which are very, very restrictive in what you can and cannot do and how you develop a story. |

|

|

| ... | Even 30 years later he was still imprinted by that. So I think that's what you're referring to. And that never bothered me because I grew up reading every science fiction book there was and science fiction comics and and I enjoyed all of it. But in the 1960s Michael Moorcock embarked on this crusade to apply literary techniques to science fiction, and most New Worlds contributors adopted this as a crusade. I was ill-suited to it, since I had no literary background. Barry, likewise, wasn't "politically correct" in the new regime. But I felt, and I think Mike Moorcock felt, that Barry's ideas were so good we didn't really care if the writing was sometimes a bit pulp-flavored compared with some of the other people. Unfortunately, the further New Worlds moved toward literary pretentions, the less appropriate it became as a market for Barry. I think he realized this, and stopped contributing stories after a while. It seems to me that this kind of visionary science fiction is the hardest kind of work to sell, and sometimes the hardest to swallow - the average reader might not 'get it' and the scientifically oriented people might laugh at the ideas being too wild and impossible. Do you think that's true, and might it apply here? |

... | |

| ... | Yes, I think you're absolutely right. One of my favourite stories of Barry was about "what if the universe was completely filled with rock." And each of us is living in a little bubble in the rock. In other words, the basic premise of the story was impossible because the universe is not full of rock. But he's like, "what if it was?!" And he described their attempts at space travel which would be basically digging tunnels through the rock. And he saw immediately that the biggest problem would be that when you dig a tunnel, the stuff you dig out will never be as compact as it was so you lose space all the time. And so his people are constantly afraid of losing what little space they have. It's just a brilliant vision but I could see that most people would say "what's the point?" It's about something which doesn't exist. |

... | |

|

So in a way he fell between science fiction as it's conventionally done and fantasy where people really don't care if it makes sense or not; they just believe it anyways. And that's an unhappy place to be, halfway between two categories. It's usually fatal commercially speaking. Barry's great admirer in America was Donald Wollheim, who created Ace books. Wollheim went on publishing Barry when no one else was willing to do so really. And then when Wollheim died, that was very bad news for Barry. It's a really tough business to be in, writing science fiction. A. E. van Vogt said that the typical science fiction writer's active life is ten years. And before that you don't quite fit into what the current fashion is, and after that you've been left behind by the current fashion. I think there's a lot of truth into that. It's really hard because the movies have completely changed the whole field. Yeah, and also computer games these days.. |

... | |

| ... | Sometimes I talk to people who are really into computer games or computer programming, and they would like to read more science fiction that really makes conceptual sense, and is clever and innovative, but they can't find it. Part of the reason is that there are very few editors anymore who understand that kind of science fiction. It's really like talking about the old, dead history of an obscure branch of literature, I'm afraid. Wollheim was... how can I put it? He was cheap. But at least he did understand good science fiction when he saw it. And when he died.. he was kind of the last of an era. After that, where do you go? David Hartwell, maybe. He never got over his terrible disappointment of running the best science fiction line there was, Timescape books. And then it never made enough money and so he was fired, basically. So the editors are being bruised and taught a lesson along with the writers. Everyone is forced to face the fact sooner or later, if you try to be too clever, it doesn't sell, at least not in this country. I think it does in Japan. |

... | |

| ... | Sometimes I think the people who used to write this kind of science fiction yesterday are doing 'real' science today; trying to convert those old ideas of matter transmission, FTL and so on into reality, while the actual fiction is slowly turning into a branch of marketing, published by accountants.. And they're not very good accountants (laughs). If they were making a lot of money by ruining science fiction, I would have a little more sympathy for them. But they're not really making that much money. Harry Potter is making a lot of money. That's the trouble with publishing. It's full of people who say "we're desperate to sell more books so we're going to appeal to a wider audience and to do that we're going to make science fiction a little easier to understand." What that means of course is that they're going to take away all the intelligence from it. And then despite this bold plan to make money it doesn't really do very well, with a few exceptions: Judy-Lynn Del Rey, she did it very well. She made it so awful it found a market. |

... | |

| ... | But no, to me the discussion of conceptually rich, innovative science fiction versus crowd-pleasing stories is like talking about the past relationship between Finland and the Soviet Union. That's over. And science fiction as it used to be practiced is over. Much to my sadness. You say science fiction writers are writing non-fiction and to some extent that is true. Greg Benford is trying to write non-fiction. Writing speculative nonfiction is just a different way to reach an audience, and also reflects a feeling of impatience because a lot of us really believed we were going to have colonies on moon by now and immortality drugs and we get impatient that it didn't happen. And you start thinking that well, maybe I should come back to the real world and push things a little bit there and try to make people think more in these terms, speed things up a little so that some of this interesting stuff can happen before I die. That's my view anyway. |

|

|

| ... | What about tomorrow - will there be new concepts if there are no real science fiction writers to invent them? This is probably putting too much weight on the genre but perhaps it could be extended to arts in general - might this cause a stagnation in discovery, which may already have happened, like with music or movies - will the old be endlessly recycled? Is science perhaps the art form of the future? Very interesting question. Let's do an alternate universe in which Judy-Lynn Del Rey never started editing science fiction and George Lucas never made any science fiction movies. And consequently what I would call the 1950s tradition was able to last a bit longer. The question is could they really go on finding new ideas which were kind of substantial and provocative, or were they really reaching the end of all the variations they could find on comprehensible science. And I rather suspect that maybe they really dug out all the good stuff and now they were running out of ideas. |

... | |

| ... | Because science itself - where are you going to find the new ideas? In particle physics? That's really hard and most readers don't know anything about quarks.. I rather think science got to the point where it was either too hard for science fiction, or too obscure. I'm not sure that I agree that something is being lost here - I think that maybe it coudn't be done anyways after a while. I may be wrong, we will never know. But I do like your suggestion that science fiction was useful to broaden the perspectives of scientists - there are all those NASA engineers who grew up reading Robert Heinlein. And what are they growing up reading right now? I have no idea.. so maybe you have a point there. I would certainly like to see the old science fiction still in print, that's the sad part. But maybe with the internet these things will come back into existence and people will be able to find them, that would be my hope. |

... | |

| ... | You collaborated on a story with Barry, "A Taste of the Afterlife". Do you have any recollections.. What happened was I visited him at his horrible little apartment in London and found that he had all these unfinished stories. And since I was kind of a fan of his, I said "well why don't you finish these? I'd like to read them." He was always very modest and said "oh, you know, I lost interest." So I said, "what about this one, can I finish it for you?" He said, "oh yeah, go ahead." So that's how the collaboration happened. I guess I would have done more but I didn't feel sufficiently motivated, and Barry seemed so uninterested in the whole collaborative idea. Also, we were paid so little money in those days, if you split it between two writers, there was virtually nothing! Actually, I was thinking it might have been your idea, considering your currents interest in cryonics and life-extension; afterlife I guess is vaguely going to that direction.. Yes. Maybe that's why it appealed to me, that I've always had a problem accepting the idea of death. But it was Barry's idea. I tried to imitate Barry's style a little bit too, so really I was just trying to finish what Barry had started in a way which was as true as possible to his conception and his style. |

|

|

|

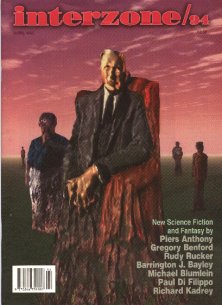

Later on you started editing New Worlds and also were the guest editor of Interzone. So you've bought several of his stories. What is it that appeals to you in his work? Well, it's really just the ideas. A good Barrington Bayley story will give you an idea which is unlike anything you've ever read anywhere else. And there are very few writers I can say that about. Plus I'm always aware that he's not sufficiently appreciated and he always could use the extra bit of money. So anytime I've had an editing position I've always tried to publish Barry. And when I was a book editor in New York, a couple of times, I tried to get books of his into print. I can't remember exactly what happened.. I think I was never an editor long enough to see one all the way through. And I think in one case another editor came along and didn't like what Barry had written and so he had to sell it somewhere else. Publishing is full of these awful stories. One editor disappears and another turns up and the writer gets stuck somewhere... |

... | |

| ... | Has his work had any influence on your own? No. And in a way I think that's why I like his work so much in that it's something I absolutely cannot do myself. It's like reading James Joyce or something, except it's in ideas rather than in style. I look at it, I'm really impressed and think "wow.. I couldn't do that." And that's what I admire about it. Because I don't get that kind of idea. It just doesn't happen to me. this interview is copyright 2000 ©

by Charles Platt |

... | |

| ... | comments? please include your email and name for a response. |

Barrington

Bayley Charles Platt |

|

[home]